![]()

TEXTUAL

LINKS

(linked notes)

Précis

Attribution and Evidence

My case for Ephelia's authorship in Lady Mary Villiers comprises, in my view and in that of several seventeenth-century specialists who have assessed the case, such as John Shawcross, James Thorpe, Anne Barbeau Gardiner, and the several peer reviewers and publishers of my work on this complex subject since 1995, a persuasive working hypothesis. The recent find of the 1679 broadside poem on the Popish Plot (Appendix D) -- the 'smoking gun' of the Villiers case -- would now seem to elevate or upgrade the status of my research from hypothesis to an attractively convincing attribution.

In formulating my arguments, I have relied on the scholarly precedent of David Vieth's "principle of probability," which relies on internal, circumstantial evidence as a legitimate criterion of textual criticism and attribution, including speculative attribution. As Vieth explains, this principle evolved as a means of dealing with a very large category of bibliographically complex poetic texts in an age of fugitive, anonymous, and pseudonymous literature; "this special class consists of poems for which no authoritative [manuscript] version is known to exist, which circulated in manuscript for a time after their composition, and which were finally printed..." (Attribution in Restoration Poetry... 7, 37-49, ff).

"Probability"(closely reasoned inferences based upon a nexus of internal and circumstantial 'evidence' within unattributed text) continues to find favor in the attributional practice of present-day scholars of contested and obscure(d) early-modern text (Vieth's "fugitive" literatures). In concert with Vieth's work and with the methodology of the Villiers attribution for the 'Ephelia' texts (1995-) is Samuel N. Rosenberg's important essay, "Colin Muset and the Question of Attribution" (Textual Cultures, 1:i [Spring 2006], pp 29-45), wherein Rosenberg discusses his and Christopher Callahan's attributional procedure in assembling a new edition of the songs of thirteenth-century trouvère, Colin Muset (Paris: Champion, 2005). As Rosenberg explains, the new Muset attributions derive from a prominent frequency of integrated authorial "signatures" in heretofore unattributed texts by Muset (this archive adopted a similar word, "thumbprints," in early drafts of this document dating from the mid-1990s); these "signatures" collectively support a reasonably inferred, circumstantial case for authorship. The close research of Rosenberg and Callahan demonstrates thematic, grammatical, and stylistic affinities, as well as a congruence between texts/allusions and known facts of Muset's biography and work, and so forth. The recent Muset attributions, much like the present attribution of the Ephelia texts to Mary Villiers, not to mention nearly all attributional work on pre-1700 English verse, relies in large measure upon just such an approach. As Vieth, Rosenberg, Callahan, and this author respectively concur, these attributions may never have an absolute certainty of authorship, but they are persuasively grounded with reasonably probative 'evidence' cleverly integrated into text. In some cases, these marks of authorship are witty and wily, drawing upon graphics, typography, title-page vignettes, encoded frontispieces, veiled autobiographical and coterie allusions, and the like. There is no external authenticity, in the cases of Muset, Ephelia, and the many verses by Restoration writers discussed by Vieth in his seminal work on attribution, but there is the close and vigilant eye of the researcher who recognizes embedded, self-identifying "signatures" or "thumbprints" of authorship within the body of work being examined, and judges them to be probative. The author is grateful to Dr Rosenberg for cordial access (Summer, 2006), and she looks forward to continuing communication.

Section I. Literary Picklock

Condensed Summary

Because this essay includes sound, which requires significantly more electronic "space" than text or image, I have had to abridge and also excerpt much complex material throughout this essay. For a fuller discussion of my Villiers attribution, readers may consult my recent essays in ANQ, my notes in Restoration and in Women's Writing, and my "Ephelia" profile in the Schlueters' Encyclopedia (second edition, 1998), all listed in this essay's Works Cited.

This essay for (Re)Soundings supplements my recent publications with the following new material: my proposed Key to Female Poems...by Ephelia (1679); my hypothesis for "Joan Phillips" as Mary Villiers's urban cover; my reading of the iconography of two of Van Dyck's portraits of Mary Villiers; Lady Mary's patronal status; and a sonic portrait by Georgina Colwell of a 1937 Ephelia setting by Dr Cecil Armstrong Gibbs. And, of course, this is the first globally-accessible, multimedia e-construction of the "Ephelia" subject.

David Vieth

Following Sir Edmund Gosse in 1885 (Seventeenth-Century Studies, 2d ed.) and Gwen John in 1920 (Fortnightly, vol. 108), David Vieth is one of the earliest commentators on Ephelia. In his classic, Attribution in Restoration Poetry (1963), he judges that "The Ephelia of Female Poems remains one of the most intriguing mysteries of Restoration literature" (344); he also comments on Ephelia's impressive poetic skills (346; 465ff), as have Lawrence Lipking and Germaine Greer, among others.

Vieth only tentatively credits to Sir George Etherege the famous lyric, "Ephelia's Lamentation," which Brice Harris has dated to July, 1675 (ELH [1943], 294-309; Wilson, Court Satires, 258-9). This famous love complaint is a verse-epistle addressed to John (Sheffield), Lord Mulgrave, in Mary Villiers's ventrilloquized voice of Mary "Mall" Kirke, a famous courtesan and jilted mistress of Mulgrave.

Following Joseph Woodfall Ebsworth, a nineteenth-century anthologist who brought fresh attention to two of Ephelia's texts, Vieth (and also James Thorpe) has essentially "fixed" the "Lamentation" as part of a linked group of satires on Mulgrave. In the closing section of this essay, I argue from fact and internal evidence that Etherege is a most unlikely candidate for the authorship of this most "female poem" in Ephelia's collected writings.

Elaine Hobby

In A Virtue of Necessity (1988), Hobby focuses on Ephelia's strong feminist voice and her uses of various traditions of love-poetry. She disagrees with "Ephelia" contrarians, such as Paddy Lyons (Glasgow University), whom she names, who judge "Ephelia" a clever hoax. Hobby concludes that most of the verse in Female Poems...by Ephelia (1679) was the work of one woman writer, working independently. Hobby is tentative, however, about Ephelia's authorship of the controversial "Lamentation" to Mulgrave and the concluding five lyrics in this interesting gathering of work.

Having failed herself in the 1980s to find a candidate for Ephelia's authorship, Hobby adamantly believes that all efforts to identify Ephelia emanate from arguments unprovable and unknowable.

Though Professor Hobby is not in agreement with my work on Ephelia, she has brought strong attention to the poet's writings.

Germaine Greer

Greer's record on the Ephelia subject reveals both fascination and ambivalence. In her anthology, Kissing The Rod (1988), she supports the nineteenth-century tradition of Ephelia as a literary hoax put over by a playful cabal of Restoration wits. Yet, she concedes that Ephelia is a "a far better poet (or group of poets) than she is currently being given credit for" (31). But in 1989, in her edition of some uncollected verse of Aphra Behn, Greer proposes the courtesan Cary Frazier as Ephelia (even though, according to Greer, Frazier both "is and is not 'Ephelia'"). Then, in 1993, in an unsolicited screed-review in TLS of my edition, Poems by Ephelia (1992, 1993), Greer reverts to her original position of 1988, reasserting the old line of Ephelia's fictionalization. Greer again shifts ground in Slip-Shod Sibyls (1994), where she includes "Ephelia" in a class of bonafide woman poets: "We know a good deal about her [the poet Katherine Philips], much more than we know of Aphra Behn or 'Ephelia'" (147).

In all fairness to Dr Greer, her work as an anthologist and as an editor of early-modern English women poets has brought important attention to the verse of 'Ephelia' and to the seductive subject of her identity.

Wilson (and others)

In a detailed review of my edition of Ephelia's work, Katharina Wilson (University of Georgia), a senior specialist on early women writers, observed that "the rocky tradition of Ephelia's fortunes begs comparison with those of Hrotsvit of Gandersheim, whose writings were long considered clever forgeries by male German humanists; and, for a time, her canon was nearly cut in half. The authenticity of Hrotsvit's texts was conclusively established in this century by the discovery of new manuscript evidence [by Wilson]. Mulvihill's findings and cautiously tendered 'formulations' have now put elusive Ephelia on a similar track" (American Notes & Queries, Winter '97: 50).

In addition to my contribution to the Ephelia debate, readers may be interested in other reconstructive commentary, listed in Works Cite", by Gwen John, Elaine Hobby, Judith Page, and Marilyn Williamson. For responsible commentary by reviewers of my edition, see citations to Georges Lamoine, Beverly Schneller, Elizabeth Penley Skerpan, and Janet Ruth Heller, who contributed an illustrated, two-page feature-review to the magazine, Belles Lettres.

Samuel J. Hardman (Commerce, Georgia), a student of Van Dyck's English portraits, speculates that the courtesan "Betty" Felton might have been Ephelia. In a solicited two-page assessment of his hypothesis (14 March 1996), I demonstrated to Hardman that his unpublished jottings on Lady Betty, while interesting and original, did not align with Ephelia's writings, nor with recorded facts about Betty. Ephelia's voice, especially in her verse after 1660, is not that of sweet and twenty (See "Phillida," Appendix A.) For Hardman's contribution to my Villiers attribution, see Section III of this essay.

H B Wheatley

In 1885, Wheatley contributed an undocumented, one-line identification of "Ephelia" as "Mrs Joan Phillips" to A Dictionary of Anonymous and Pseudonymous English Literature edited by Halkett and Laing (VIII: 1885). Wheatley may have found Joan Phillips in the work of two of his prominent bibliophilic contemporaries, Peter Cunningham and the Rev. John Francis Stainforth. An annotated copy of the sale catalogue (166 pages) of Stainforth's famous library, which included a copy of both editions of Female Poems...by Ephelia (1679, 1682), is preserved at the New York Public Library.

Though Wheatley was certainly closer to the primary materials than today's scholars, he, as most bookmen of his day, was not sympathetic to women writers. In point of fact, feminist researchers have had to work very hard these last few decades to correct errors which emanated from the early canonical work of several nineteenth-century dons.

Most extant copies of Ephelia's work include a "Joan Phillips" annotation by owners and booksellers over the centuries. But who was "Joan Phillips"? It is not entirely preposterous, in view of Ephelia's probable identity in the tricksy 'Mall' Villiers, that "Joan Phillips" was yet another alter-ego of Mary Villiers, an urban identity or cover which allowed this inventive Duchess easy access to the colorful street culture of Restoration London. Such an hypothesis is compatible with Mary's creative character and delight in madcap capers; and, as I document later in this essay, such a speculation would explain Aphra Behn's playful reference to "a Poet Joan" and Robert Gould's gritty vignette of Behn and Ephelia as a literary duo (Aphra Behn). Within the constricted confines of the Court, Mary Villiers was the pseudonymous writer, Ephelia; on the streets of Restoration London, she was "Joan Phillips." A woman of imposed multiple identities all of her long life, Mary Villiers, in the 1660s and 1670s, finally had the freedom, time, and personal space to recreate herself through multiple poetic voices and identities. From her privileged position at Court, she had the resources and surely the talent to bring off such trickery.

Aphra Behn (and also Robert Gould)

In her amusing remarks on the literary scene in the Prologue to Sir Patient Fancy (1678), Behn writes, with characteristic good-humor,: "Nay, even the Women now pretend to Reign, / Defend us from a Poet Joan again!" Contrarians hold that "Poet Joan" is a typesetting error for "Pope Joan." But this explanation falls short on two grounds: (i) Behn's context at this moment in the prologue is literary, specifically women writers, not women (cross-dressed or otherwise) in Church history; and (ii) the monosyllabic "Pope" fails to satisfy the metrical value of the line in which it appears. See my extended letter, "Poems by Ephelia," TLS (3 September 1993).

Behn's "Poet Joan," as I explain in my H.B. Wheatley link, could have been Mary Villiers in her urban persona of "Joan Phillips." Behn's circle included blue-bloods of the Stuart court, as well as denizens of Grub Street. Behn's reference to "a Poet Joan" may suggest Behn's knowledge of 'Mall' Villiers's frolics. The lovely homage, "To Madam Bhen" (a contemporary alternate spelling of "Behn") in Female Poems...by Ephelia, discloses a personal and literary link between these two writers, not to mention Behn's longstanding membership in the Villiers family-circle. She, in truth, tenderly elegized the passing of George Villiers, second Duke of Buckingham. Charles II's Court Wits included only two women poets who were clever enough to negotiate such company: Aphra Behn and Mary Villiers.

In 1683, Robert Gould, a talented poet-playwright and protegé of John Oldham, spun off a gritty urban sketch of Behn and Ephelia as a sororal team of poet-prostitutes, working the literary fringe. In the following excerpt, an angry Robert Gould thinks that either Behn or Ephelia had penned a response to his verse-satire, "Love Given O're" (1683), whose shocking misogyny kept the female pen busy for twenty years:

Ephelia! poor Ephelia, ragged Jilt!

And Sappho, famous for her gout and gilt.

Either of these, tho' both debauch'd and vile,

Had answer'd Me in a more decent Stile.

Yet Hackney Writers; when their Verse did Fail

To get 'em Brandy, Bread and Cheese, and Ale,

Their Wants by Prostitution were supply'd.

Show but a Tester, you might up and ride:

For Punk and Poetess agree so Pat,

You cannot well be this, and not be That.

(A Satyrical Epistle, [1683], 1691)

In "English Femmes Savantes at the End of the Seventeenth Century," A.H. Upham valuably provides a list of feminist verses inspired by Gould's poem (JEGP 12 (1913): 10-16). Sarah Egerton's "Female Advocate" (1687) is the most notable of these. I contributed the first profile of Egerton to Janet Todd's Dictionary of British & American Women Writers, 1660-1800 (1985, 1987). The reigning specialist on Sarah Egerton is Jeslyn Medoff.

Thomas Newcombe

In his poem, Bibliotheca (1712), Thomas Newcombe includes a catalogue of women poets of the preceding age, a list which includes a "Phillips, who in Verse her Passion wrote." Newcombe's allusion could not refer to the demure Katherine Philips, as Roger Lund suggested (Restoration, Fall, 1989; see my correction, Scriblerian, Autumn, 1990: 87-8), but rather to the forceful lyrics of Ephelia, who, evidently, was associated at this time with the "poet Joan" (Joan Phillips) of Behn's circle. Newcombe's allusion is valuable, as it illustrates the continuity of a developing link in the eighteenth-century between the Ephelia poet and Behn's "poet Joan" -- the Joan Phillips whom I suggest 'Mall' Villiers invented as a cover for her literary life outside the constricting confines of the Court and her ducal status.

Joseph Woodfall Ebsworth

Ebsworth provides tantalizing information in a footnote to his text in the Roxburghe Ballads of "Ephelia's Lamentation,": "One of Mulgrave's mistress was 'humble Joan'" (IV 1883: 568). In view of the four-way intersection, consisting of Behn's "Poet Joan," Ebsworth's 'humble Joan' (a mistress of Mulgrave), Gould's "poor Ephelia, ragged Jilt," and Newcombe's "passionate" female poet "Phillips," we may reasonably deduce that "Joan Phillips" was a living, corporeal presence, albeit a minor one, in the Restoration literary scene, and that Ebsworth's misleading annotation had merely confused the author of the "Lamentation" ("Joan Phillips") with the persona she adopts and ventrilloquizes in these lines, that of Mulgrave's cast off mistress, Lady Mary ('Mall') Kirke. When Ebsworth refers to Mulgrave's mistress as "humble" Joan, I imagine he was drawing upon some information on Joan Phillips (Mary Villiers's urban alter-ego) as a quiet spectator of the literary scene. And would this not align with such a subterfuge?

Sir Edmund Gosse

In the first dedicated discussion of Ephelia by a literary critic, Gosse suggested that if "Ephelia" had been "Joan Phillips," she might have been the daughter of the celebrated poet, Katherine ("Orinda") Philips (Seventeenth-Century Studies, 2d ed., 1885). Gosse's "wild rumor" (as he called his own hunch) was, indeed, "wild," and soon overturned by John Pavin Phillips of Haverfordwest, Wales, a descendant of the poet. On the basis of inscriptions in a family Bible, this relative showed that none of "Orinda"'s daughters were named Joan and none (alas) were writers (N&Q 1958, vol. V: 202ff).

Yet, some rumors die hard; for we find "Joan Phillips" (as Ephelia) inscribed in several extant copies of the rare Female Poems...by Ephelia. "Joan Phillips" is also listed as "Ephelia" in the principal American and British library catalogues, as well as in Donald Wing's Short-Title Catalogue. According to my present reading of the case, "Joan Phillips" was Mary Villiers's urban cover; and the longstanding attribution of Ephelia's work to Joan Phillips is not entirely wrong: it simply names one alter-ego (Ephelia) with another (Joan Phillips). Behind them both, was the chuckling Mary Villiers.

It may be some time before my new case is fully digested and hopefully accepted, at which point Wheatley's "Joan Phillips" would be superseded bibliographically by Mary Villiers, the newly reclaimed Stuart duchess introduced in Section II of this essay. And this is all now underway: the "Ephelia" records in the ESTC/UK and ESTC/NA were updated to reflect Mary Villiers, in July, 2001.

Sir George Etherege

In his notes to two texts associated with the "Ephelia" poet, Advice To His Grace (ca. 1681) and "Ephelia's Lamentation (ca. 1675)," Ebsworth names Sir George Etherege and his fellow Court Wits as the writers behind the "Ephelia" pseudonym (Roxburghe Ballads, IV 1883). The attribution of Ephelia's work to Etherege originates in a single piece of circumstantial evidence on a manuscript copy of a poem now attributed to George Villiers, second Duke of Buckingham, which I take up at length in the closing section of this essay.

As James Thorpe observed in his edition of Etherege (1963), it is has been the absence of incontrovertible evidence of Ephelia's authorship, rather than proof positive of Etherege's, which has permitted "Ephelia's Lamentation" (the poet's famous lyric to "Bajazet" [John Sheffield, Lord Mulgrave]) to remain in Etherege's canon since the eighteenth century. Yet, the tradition of Ephelia's authorship in Etherege and his circle has persisted, in editions of Etherege by James Verity and by Thorpe; in a recent collation of this poem by Peter Beal (Index of English Literary Manuscripts, 1625-1700 [II,i, (1987): 449-50]); and in recent work on Rochester by Edward Burns and Michael Stapleton.

The probable source of Ephelia's putative corporate authorship may originate (innocently enough) in a footnote in an eighteenth-century edition of Rochester's work: "Having before inserted his Lord's Answer to the following letter [i.e., Rochester's reply to "Ephelia's Lamentation," 1679], several Gentlemen desir'd us to add the Letter itself [i.e., the poem, "Ephelia's Lamentation"] (Works 1707; emphasis added). These "several Gentlemen" would soon become "Ephelia" herself.

Warren Chernaik

In a deconstructionist treatment of Ephelia's authorship in Philological Quarterly (Spring, 1995), Chernaik adds formidable heft to the old view of Ephelia's fictional authorship. Strategically downplaying Ephelia's Stuart broadsides, Chernaik focuses almost exclusively on Ephelia's collection of 1679. His analysis centers on the several "confusing" rhetorical "voices" he hears in Ephelia's poems; and his essay concludes inconclusively.

Revealing a fundamental ambivalence, Chernaik closes unsatisfactorily, if not facetiously: "It is possible that several authors, male and female, contributed to a collaborative enterprise; it is possible that the volume is the work of a single female author or a single male author. 'Ephelia' does not exist, except as embodied in the poems" (167). As The Scriblerian editors wrote in a recent brief notice on this essay, "Well, someone must have written these poems."

I am grateful to Professor Chernaik for his even-handed treatment of my earlier work (1992) on the 'Ephelia' subject, which he found to be "impressive," "heroic," even "brave." While he and I are not in agreement, we do share a commonality of interests in this complex case. Unlike other commentators on my work (Germaine Greer, Michael Caines, et al.), Chernaik has represented my research in a fair, unbiased fashion.

Anne Phillips (Prowde) Proud of Shrewsbury

Evidence supporting this "tentative speculative candidate" of 1992 derived from provocative genealogical and heraldic intersections, discussed (with images) in the third section (pp. 65-76) of my edition's eighty-eight-page "Critical Essay." This candidate, whose personal circumstances and family lineage connected with certain features of the "Ephelia" subject, was essentially a faceless candidate. Proud has since been superseded by a much more accessible and forceful candidate, introduced in Section II. The publisher of my edition, Norman Mangouni, of Scholars' Facsimiles & Reprints, observed, "You were wise not to overplay your hand with that first candidate." And the late Arthur Scouten, a co-dedicatee of this essay, had this to say to me in 1991 about Anne Proud: "No, this candidate is not right for your poet, though you've built an attractive case. 'Ephelia' is someone very big. Look at the aristocratic hand of the 'Isham' autograph, look at the licensed broadside to Charles. You'll find her. Keep at it."

My first search for "Ephelia," regardless of the veracity of my then candidate, was nonetheless an essential and useful exercise. The edition's apparatus of six appendices, e.g., involved a systematic organization and synthesis of a massive amount of material, accreted since the seventeenth century. In addition to the reviews listed in "Works Cited," my labors have been appreciated by some "Ephelia" contrarians. Warren Chernaik judges the edition "impressive and valuable," even "heroic" ("Ephelia's Voice," PQ, Spring, 1996); and Trevor H. Howard-Hill judges the edition "a valuable contribution" (PBSA, Spring, 1993).

Judith Page

In this first dedicated thesis on "Ephelia," "Fashioning An Identity of the Libertine Woman in Female Poems...by Ephelia" (Oklahoma, 1995; Vincent Liesenfeld, director), a project inspired in part by my delvings (Acknowledgments, iv), Page affirms the view of Ephelia as a corporeal female voice. She offers a reliable overview of the debate and also demonstrates "Ephelia"'s uses of various male and female Restoration typologies (libertine, whore, etc.). Her analyses are especially good in Chapter III, which discusses "Ephelia"'s poetry within the context of the poet's construction of a "multidimensional self-image." Page's "multidimensional" Ephelia and Chernaik's "Ephelia" of many "confusing voices" can now be explained in my case for the new candidate, discussed in Section II of this essay.

Georgina Colwell

Trained at London's Goldsmith's College and the Guildhall School of Music, Colwell (Albany Road, Hersham, Surrey) is a soprano specializing in English song and Leider. Ms. Colwell has recently given concerts of English composers in Italy, Spain, Belgium, The Netherlands, Russia, and throughout Britain. The Musical Director of Musicair Productions, she recently completed organizing the manuscripts of composer Peter Wishart. Her compact disk, This Scepter'd Isle (1993), includes Dr Cecil Armstrong Gibbs's setting of Ephelia's "To One Who Asked Me Why I Lov'd J.G" (Female Poems...by Ephelia, 1679), published by Boosey & Hawkes, London, in 1937. A sound clip from this setting concludes my essay. See my note, co-written with Colwell, "Ephelia Setting on CD," Restoration (Fall, 1997).

Section II: Flashpoint: "Butterfly" in My Net

Duel (Lady Mary Villiers's Duel)

A gentlewoman duelist of a female romantic rival, information supplied on Duchess Mary by the Baroness Burghclere (Villiers 140), is a creature of high color. We observe the combustible personality of the Ephelia poetess (very probably Mary Villiers Stuart, Duchess of Richmond) in her verse-letters to or about a female rival ("Mopsa") and to various courtesans for whom she had a special animus. Addressing her cousin, Barbara Palmer née Villiers (c. 1640-1709), Charles II's principal mistress in the early 1660s, for example, Ephelia displays something rather rare in 17thC English verse by or attributed to women poets: high pique. She writes hotly:

Imperious Fool! think not because you're Fair,

That you so much above my Converse are!

........

Since then my Fame's as great as yours is, why

Should you behold me with a Loathing Eye?

If you at me cast a disdainful Eye,

In biting Satyr I will Rage so high,

Thunder shall pleasant be to what I'le write,

And you shall Tremble at my very Sight;

Warn'd by your Danger, none shall dare again,

Provoke my Pen to write in such a strain.

("To A Proud Beauty," Female Poems...by Ephelia, 54-5;

see also"Proud Beauty," Appendix B)

Ephelia cues the reader to the identity of this "Proud Lady" with the description "Imperious fool," this being almost 'code' for Barbara Villiers, whose high-handed ways, especially with higher-ranking contemporaries, is often mentioned in accounts of the Restoration court. Bishop Burnet, in his oft-quoted history of the period's manners & mores, acknowledges the lady's great beauty, but emphasizes her "ravenous" and "vicious" appetites, especially her "foolish but imperious" character (History [1753] I.132; S M Wynne, "Barbara Palmer née Villiers...," Oxford DNB [2004). If there was a word for 'Madam Palmer', it was imperious; thus, Ephelia's (disclosing) word choice in the above poem.

Back to Mary's duel. In the English edition of D'Aulnoy's Mémoires, discussed in this document's link, "Sources - Character Profile," we find a reference to the quick temper and histrionic behavior of Mary Villiers, a reference which may refer to the duel which Burghclere only mentions. Thus, D'Aulnoy: "Her [Lady Mary's] jealousy of Lady Shrewsbury, whom Mr Howard had loved... had caused her [Mary Villiers] to break out in such a way as to destroy in one moment all the measures she had carefully taken to guard her secret [her clandestine romance and eventual marriage to Howard in 1664]" (234).

Dueling was not foreign to Lady Mary's experience, of course. Her father, brother, and second and third husbands were capable duelists; in fact, her third husband, Colonel 'Tom' Howard and her brother, George Villiers, second Duke of Buckingham, were fatal duelists, who fought their romantic rivals to the death. From childhood, Mary Villiers was raised in a masculine universe of glamorous, charismatic men. The tradition of her duel, mentioned by Burghclere, certainly accords with Mary's temperament, her delight in male masquerade (discussed later in this essay), and with the heavy masculine cast of her upbringing. When she (as the "brisk and jolly Richmond") and Prince Rupert of the Rhine, her ardent suitor of the 1640s, are accused by Puritan propagandists in A Parliament of Ladies (1647, [Henry Neville]) of frequently "beating up of Quarters and other unlawful sports" at Kate's in Covent Garden, doubtless a reference to the home of Catherine (Howard) Lady d'Aubigny (familiarly, "Kate"), we are valuably given not a sexual reference particularly, but rather a reference to what Mary and Rupert did together: they enjoyed the practice of such "unlawful sports" as dueling, shooting, and probably gambling. Certainly, Mary had a fencing-master nonpareil in the glamorous Rupert of Civil Wars fame, the sad "Phylocles" in Mary's clever alchemical poem on friendship between the sexes (Appendix A).

For locations on the vogue of fencing and dueling among gentlewomen of the Restoration court, see Allan Fea's chapter on the captivating bisexual adventuress and short-lived mistress of Charles II, in 1675, Hortense de Mancini, Duchesse de Mazarin, whose skill in fencing was matched by her expertise as a shootist and gambler; Charles called this dark beauty the finest woman he had ever met (Some Beauties of the Seventeenth Century [1906], 1-26; Hutton 336-337).

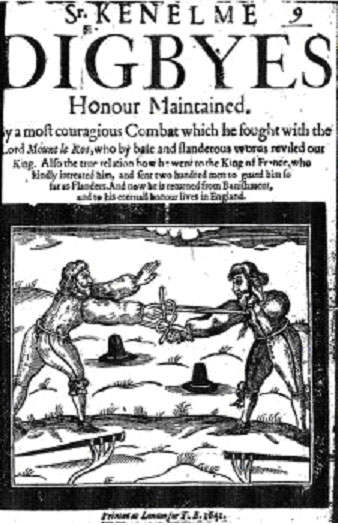

As we can infer from Sir Kenelm Digby's Honour Maintained (London, 1641), noblemen at the Stuart court flaunted their reputation as duelists, regardless of the Crown's serious legislation and fines against public dueling. The above image, from Early English Books Online, is from the 1642 edition, British Library copy; see also the handsomely illustrated website, Court of Chivalry, constructed by Steve Rea and Richard Cust, Birmingham University, UK: http://www.court-of-chivalry.bham.ac.uk/antiduelling.htm.

Scholars have yet to investigate 17thC noblewomen's participation in fencing and dueling, however. In view of the playful vogue in male masquerade (transvestism) which caught the fancy of a few sporting women at the court of Charles II, dueling and fencing surely would have appealed to certain vivacious women of that colorful age. Allan Fea and also Winifred (Gardner), Baroness Burghclere, have identified two such women who evidently favored these amusements: Hortense (Mancini), Duchess of Mazarin (Fea, Some Beauties of the 17th Century [London, 1906, 1907; 82 portraits], Chapter I) and Mary (Villiers, later Stuart), Duchess of Richmond (pseud., 'Ephelia') (Burghclere, Villiers [NY & London, 1903], p 140).

Sources: Biographical Profile of Lady Mary Villiers

In one of few extant sketches of the life of Mary Villiers, John Heneage Jesse writes, "Of one whose fortunes were so splendid, whose conversation is said to have been fascinating, and whose beauty was the envy of her contemporaries, it is extraordinary how few particulars are known" (Memoirs of the Court of England V [1813], 203).

Compounding the relative difficulty of constructing a first biographical profile of Lady Mary is her long list of names. Her parents, guardians, and intimates called her "Mall" and "The Lady Mary." Her younger brother, George Villiers, second Duke of Buckingham, called her "My Duchess" and, as I suggest below, "My Muse." Bibliographically, Mary Villiers is frequently confused with such female namesakes as Mary (Villiers née Beaumont), Duchess of Buckingham (her mother-in-law); Francis (Stuart), Duchess of Richmond (her young niece and the "Beauteous Marina" in three verses in Female Poems...by Ephelia); Mary (Villiers née Fairfax), Duchess of Buckingham (wife of her brother, George Villiers, the second Buckingham); a later Mary Villiers, daughter of Sir Edward Villiers, Maid of Honor to Queen Mary, and wife (in 1691) of Lord William O'Brien; and an earlier Mary Villiers, elegized by Thomas Carew (ca. 1630s?). The profile of Mary Villiers in the upcoming New DNB lists her as "Mary, Lady Howard."

There is little extant manuscript material by or about the new candidate, other than a cache of love-letters between her parents, which mention Mary's antics and clever impersonations when a precocious child (Harl. MSS 6987:117-119; Goodman II:260-67; Jesse III:84ff; Thomson II:232ff; Lockyer 153ff; Gibbs 91ff). Most of Mary Villiers's personal papers reportedly went down with a baggage ship in the late 1640s (Hamilton 187); and, to date, no handwriting sample of hers has been catalogued in manuscript collections at the Bodleian, the British Library, Castle Howard, Wilton House, and at Nottingham, where she maintained a residence during the 1640 and 1650s (Burghclere 53). I, therefore, had to rely on shards of information in contemporary materials and in reliable secondary sources in assembling my biographical and personality profiles for this essay.

Henriette-Anne, Duchesse d' Orleans ("Minette," the first "Madame")

"Minette"'s correspondence with her older brother, Charles II, from 1659 until her premature death in 1670, has been gathered and published by Cyril Hughes Hartmann (London, 1924); and more recently by Ruth, Lady Norrington (Peter Owen, 1996). The letters valuably document clandestine intrafamilial communications on serious political issues and especially foreign policy, such as the Secret Treaty of Dover, in which Minette's secret diplomacy played a role. The correspondence also documents the role of their childhood friend, Lady Mary Villiers, my candidate for "Ephelia," who distinguished herself as an unofficial conduit of royal intelligence during the Interregnum and Secret Treaty of Dover.

Script

The elegant hand of the "Ephelia" autograph, being a draft-elegy on Sir Thomas Isham, preserved at Nottingham, is very similar, though not identical, to the script of her younger brother, George Villiers, second Duke of Buckingham. A photograph of Ephelia's "Isham" elegy is reproduced in my edition of 1992, 1993. A fold-out photo-facsimile of George Villiers's informal script, being a letter to his wife, Mary Fairfax, is in Burghclere's Villiers (facing p. 88). Photographs of Villiers's autograph verse, in his surviving commonplace book, are in John O'Neill's essay on Villiers, DLB 80:245-262.

Sources: Character Profile of Lady Mary Villiers:

In reconstructing a character profile of Lady Mary, I have relied chiefly on a book of reminiscences, Mémoires de la Cour d'Angleterre (1694), by Marie Catherine le Jumelle de Berneville, the Baroness D'Aulnoy (or Dunois), a frequent guest at the Restoration court during the 1660s and 1670s (Wall 61-63). The Mémoires was so sensational that it served as a model for the famous Mémoires (1701) of Philibert Comte de Gramont; it also initiated a vogue in chroniques scandaleuses, which culminated (in England) in the popular novels of Delariviér[e] Manley in the early eighteenth century. It was not until 1913, however, that D'Aulnoy's Mémoires received a fully annotated and apparently reliable English-language edition by Lucretia Arthur (Mrs William Henry Arthur). So detailed are D'Aulnoy's memoirs and so generous the editorial annotations by Arthur that sections of the volume serve as a partial clef to Female Poems...by Ephelia; for my clef to this collection, see Appendix A.

I also found useful information in biographies of the Stuarts, the Villierses, and of members of their interrelated circles, such as Prince Rupert. (These sources are listed in this essay's Works Cited.)

For contemporary work on butterflies, I delved into the pre-Linnaean classic which A.S. Byatt's gothic novella, Morpho eugenia (film adaptation, Angels & Insects, 1995), may bring back into currency: Dr Thomas Muffet's handsomely illustrated folio of 326 pages, the Theatrum Insectorum (1634; tr., 1658). His anachrophobic daughter, Patience Muffet, is the "Little Miss Muffet" in the famous English childhood rhyme, which mentions insects. In contemporary materials, variants of "Muffet" are "Mouffet" and "Moufet."

Searches in the summer of 1995 at The American Museum of Natural History in New York City into other relevant entomological classics, by Maria Sibylla Merian, Jan Swammerdam, and Ulysses Androvandi, though pleasureful, were not fruitful.

Sir Anthony Van Dyck, his Portraits of Mary Villiers

To date, several portraits of Mary Villiers have been recorded by distinguished specialists.

She appears, full-length, in at least three group portraits: The Duke of Buckingham and His Family; The Widow and Orphans of the Duke of Buckingham; and Philip (Herbert), Lord Pembroke and His Family (Image 6).

Full-length double portraits include: Lady Mary Villiers and her cousin, Charles Hamilton, Lord Arran, as Cupid (Image 8); and Lady Mary Villiers, with her Dwarf, Mrs Gibson (Image 11a).

As single-subject studies: Lady Mary Villiers with her ducal coronet, as backgroung trope; Mary Villiers as St Agnes, Patroness of Brides (subject is sitting; with lamb and palm branch as tropes); Lady Mary Villiers, holding downwardly a small bouquet, and pressing a black decorative bow to her heart (a three-quarter length); and Mary Villiers holding a bouquet of flowers, from an engraving by Hollar after Van Dyck (subject sitting, and misidentified in the portrait as "Lady Elizabetha Villiers"; photo, D'Aulnoy, Memoirs, facing p. 112 ). J.T. Cliffe, in The World of Country Houses in the Seventeenth Century (Yale UP, 1999), provides the new information that a portrait of Lady Mary (which Cliffe fails to identify) was in the collection of a cousin of the poet-laureate, John Dryden, Sir Gilbert Pickering (1613-1618) of Titchmarsh Hall, Northamptonshire (p. 44).

Lady Mary's father was instrumental in Van Dyck's success in England, as Buckingham negotiated Van Dyck's pension from James I in 1620 and effectively secured the painter's position at the Stuart court. Buckingham also purchased several Van Dycks through his arts advisor and agent, Balthazar Gerbier, who produced a juvenile sketch of Mary Villiers, preserved in the British Museum and mentioned in family correspondence (Lockyer, 153).

Graham Parry has observed that Van Dyck cultivated a special relationship with Stuart court poets, and that no other painter working in England received as much praise from poets ("Van Dyck and the Caroline Poets," Van Dyck 350 [Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1994], 247-60). Did Van Dyck know of Mary Villiers's literary activities? It certainly is possible. His ties to many prominent literary figures would have contributed to her lifelong preference for Van Dyck (also a devoted Catholic) as her personal painter.

For information on Van Dyck's portraits of Lady Mary Villiers, see Works Cited at the end of this archive for Sir Oliver Millar, Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr., Erik Larsen, Samuel J. Hardman, and Wilton House. See also "A Royal Van Dyck," with color image of Lady Mary, in the Discoveries link of the website of the Historical Portraits gallery, Mayfair, London (http://www.historicalportraits.com/discoveries.asp). I am grateful to James Mulraine, Associate Director, Head of Research, Historical Portraits, for kindly acknowledging my work (Summer, 2003) in the gallery's detailed commentary on Lady Mary Villiers and for valuably bringing my attention to Lady Mary's link to the Legge line, barons of Dartmouth.

"Muiopotmos; or, The Fate of the Butterflie" (1590)

In Spenser's cautionary allegory on the death of the butterfly, Clarion, dedicated to his kinswoman and sometime-patroness, Lady Elizabeth Carey née Spenser, wife of Sir George Carey, we find some of the loveliest lines in all of literature on the spectacular beauty of lepidoptera, lines apropos the high color and preeminent loveliness of Lady Mary Villiers, the "Butterfly" of the Stuart court:

Of all the race of silver-wingéd Flies

Which doo possesse the Empire of the aire,

Betwixt the center'd earth, and azure skies,

Was none more fauourable, nor more faire.

..........

Lastly the shinie wings as silver bright,

Painted with thousand colours, passing farre

All Painters skill, [Clarion] did about him dight:

Not half so manie sundrie colours arre

In Iris bowe, ne heven doth shine so bright,

Distinguished with manie a twinckling starre,

Nor Junoes Bird in her ey-spotted traine

So manie goodly colours doth containe.

(Spenser, eds. J C Smith & E. De Selincourt [Oxford, 1912; 1969 ed.], ll. 17-20, 89- 96)

I am grateful to the editors of (Re)Soundings, who unwittingly brought my attention to this text of Spenser's in an endnote to their Preface to Issue 1, no. i.

Lampoons, Mentioning Lady Mary Villiers

Among the many abusive lampoons on women of the Restoration court produced by the Court Wits, we find an occasional reference to Lady Mary as "Richmond." In the following excerpt, her amorous intrigues on behalf of Charles II provide grist for the (lampoon) mill:

Gray-growing Richmond has just right

To challenge here a place;

She has maintained with all her might

The noble whoring cause.

("A Ballad to the Tune of Cheviot Chace," Harleian MS 7319, f. 170 [ca. 1680])

A playful lampoon against Charles II, attributed to Rochester, alludes to Lady Mary's cabal on behalf of her niece, Elizabeth Lawson, and also to Lady Mary's choice in spirits. Speaking to his boon companion, Charles II, Rochester writes:

Old Richmond, making thee a glorious punk,

Shall twice a day with brandy now be drunk:

Her brother Buckingham shall be restored,

Nelly [Miss Lawson] a countess, Lawson [her father], a Lord.

("Flatfoot, the Gudgeon Taker," [ca. 1680], POAS, II:190)

An anonymous Court satire captures something of Mary Villiers's awkward intergenerational status in the second half of the seventeenth century, particularly her pride of family name:

Now Richmond, the relic, once youthful and fair,

With matronly modesty put in her claim;

Adonis, she thought, would have fall'n to her share

Out of very regard to her honor and name.

("Session of Court Ladies," Harl.MS. 7319, f. 557).

Mary Villiers's fondness for brandy may be the context of two amusing lines in "Satire on the Court Ladies" (ca. 1680):

I blush to think one impious day has seen

Three duchesses roaring drunk on Richmond Green.

(Harleian MS 7319, f. 87)

In view of her many personal losses by the late 1670s -- the death of her natural and adoptive parents, three husbands, and both children -- Mary Villiers displayed uncommon valor, and her alleged excesses are comparably innocent in a Court culture in which heavy drinking was a unisex pastime and the first of sports.

Cross-dressing

Denis de Repas, a French official at the English court, wrote to Sir Robert Harley of courtwomen's delight in transvestism: "Unless one hath the eyes of a Lynx, [which] can see through a wall, for by the face and garbe, the women are like men: they do not wear hood or gown, but only men's perwick hats and coats" (Sergeant 125). Female transvestism at the Restoration court (its social, feminist, and sexual impulses) is a rich subject, which merits more attention from scholars. We are just beginning to appreciate the popularity of this vogue or divertissement; see, e.g., Emma Donaghue, Passions Between Women: British Lesbian Culture, 1668-1801 (NY: HarperCollins, 1995).

Section III. Graphic Wit:

The "Ephelia" Portrait and Poems, Newly Decoded

Title-page Ornaments

For analyses of graphic wit in selected English printed books, see one of the classic studies on this subject by Margery Corbett and R.W. Lightbown, Comely Frontispiece: The Emblematic Title-Page in England, 1550-1600 (London, 1979); see especially, "The Decoration of the Title-page," p. 2ff, and "Devices & Emblems," p. 10ff.

"Ranging," as Butterfly Language

When "Ephelia" writes that she was "Ranging the Plain one's Summers Night," she was using the correct language for butterfly movement. Spenser's butterfly poem, "Muiopotmos" (1590), provides a precedent for such language; here is Spenser's description of the quick flight of the resplendent butterfly, Clarion:

The fresh yong flie, in whom the kindly fire

Of lustfull youngth began to kindle fast,

Did much disdaine to subject his desire

To loathsome sloth, or houres in ease to wast,

But joy'd to range abroad in fresh attire;

Through the wide compas of the ayrie coast,

And with unwearied wings each part t'inquire

Of the wide rule of his renowned sire.

(ll. 33-40; emphasis added)

Mathys

Alphonse Willems, the first of several distinguished cataloguers of the great House of Elzevier and their Dutch printing contemporaries, identifies the father-and-son firm of Severin and Adrian Mathys as operating two presses at Nonnensteeg, Leyden, circa 1646 to 1674 (Willems 422, 424). Mathys was one of several firms which produced imitation-Elzevier books; see my essay on the Elzeviers in ANQ (Summer, 1999), 23-34, 6 ills.

Transmission of Book Ornaments

As Richard Goulden has shown, printers in early-modern Europe and England commonly imitated and sometimes borrowed book ornaments from one another without legal restrictions (The Ornament Stock of Henry Woodfall, 1719-1747 [1988], 164ff). McKerrow also discusses this liberal "transfer of ornament-devices from one culture to another" (Printers' and Publishers' Devices in England and Scotland [1913], xxv). For documentation of the vogue in imitation-Elzeviers at this time, see Donald W. Davies, Elzeviers (148) and my essay in ANQ (Summer, 1999).

William Downing, Printer of Female Poems...by Ephelia (1679)

Downing is listed as a bonafide London printer in Henry Plomer's Dictionary of ... Printers (1922), 106. For background on the pro-royalist connections of the Downings to the Stuart monarchy after 1660, see the DNB and Hutton's Charles II. Plomer suggests that Downing may have printed "A Reply to ... the D. of Buckingham's Letter" (1685).

In the late 1980s, James Mosely of St Bride's Printing Library, London, generously identified for me the (conventional) typeface Downing used in printing "Ephelia"'s elegant octavo: Roman type, Great Cannon; italic type, James.

None

of Downing's other books uses the same typographical mark which appears on the

title-page of his most famous imprint: Female Poems ... by Ephelia (1679).

This suggests its non-proprietary use in Downing and also its special use in

this book project. I have not found, to date, this same mark in any other English

poetry-book of the period. For a handsome webpage, with color images, of typographic samples of Downing's work, see the Cary Collection's offerings in Downing at the Rochester Institute of Technology (Rochester, New York) at

http://wally.rit.edu/cary/cc_db/17th_century/5.html.

Jean Papillon (his wood-engraving firm, Paris)

The family firm of the Papillons flourished over three centuries. Giles Barber has valuably identified locations of Papillon ornaments (including small butterflies) in several unusual and clandestine books, which Mary Villiers may have seen, circulating on the Continent, particularly France; see Barber, "Flowers, The Butterfly, and Clandestine Books," Bulletin of the John Rylands University Library of Manchester 68, no. 1 (1985): 11-33, ills. Barber's "Butterfly" is not Mary Villiers, but Jean-Michel Papillon.

M' Lady's Spots

Supplementing my entomological reading of the word, "ephelia," is contemporary usage of "spots" to refer to stylish cosmetic patches (beauty marks) worn by courtesans and (to conceal venereal blemishes) by prostitutes. When Queen Catherine of Braganza's mother died, "the Court wore the deepest mourning; the ladies were directed to wear their hair plain and to appear without spots on their faces, the disfiguring fashion of patching having just been introduced. Lady Castlemaine was considered to appear to great disadvantage without her patches." (Strickland, "Catherine of Braganza," Lives X: 261). If Mary Villiers had been in the habit of wearing 'spots,' her choice in pseudonym could be easily explained; but, to date, I have not found anything in contemporary sources to support this. And if she were naturally spotted or freckled, she would not have been praised as a great English beauty.

1682 Title-page of Female Poems ... by Ephelia

The 1682 title-page of Ephelia's book reads: FEMALE / POEMS / On Several / OCCASIONS./ [rule] / Written by / EPHELIA./ [rule] / The Second Edition, with large / Additions. / [rule] / LONDON, / Printed for James Courtney, at the Golden / Horse Shooe upon Saffron Hill, 1684. (Wing P2031) (For a photograph of this title-page, from the Huntington's copy, see my edition, Poems by Ephelia, p. 11.)

The butterfly-swords mark does not appear on the title-page of the second edition for the simple reason that its "Butterfly" author (Mary Villiers) had "dropped" (i.e., died) by this time. The absence of this authorial emblem suggests that the 1682 collection was an unauthorized issue. The 1682 edition also lacks the strong presence of the "Ephelia" poet: the printed subscription "Ephelia" on the final page of the 1679 issue is conspicuously absent on the final page of the second issue in 1682.

The manual cancel on the title-page of the Huntington Library's copy of the second edition provides valuable information on the evolution of this book from one state to quite another. The crude cancel, executed possibly by a contemporary bookseller, changes the printed publication date from 1682 to 1684. In keeping with the facts of the present case, this correction to the book's publication date may suggest that the title-page of the second edition was reset two years too soon. According to contemporary reports, Mary Villiers died after a lengthy illness in 1685 (1684, old style). The old-style death date, 1684, corresponds to the manual cancel in the Huntington copy imprint. Evidently, the title-page of the 1679 issue was reset in 1682, but the book was not released on the market until after the author's death in 1684.

Pasted to the free back endpaper of the Bridgewater-Chew-Munn copy of the 1679 Female Poems, preserved at the Harvard College Library, is its original sale catalogue slip, which offers useful, though not entirely accurate, information on the sale and distribution of this curious book: "In 1682, the unsold sheets [of the first edition, 1679] with some additions, were issued with a new title."

Well, yes and no. While the italic and roman types of the 1682 second issue match those of the 1679 first issue, Female Poems...by Ephelia was never sold in loose sheets, but rather as a bound book, for 1s., the going rate for a small octavo (Term Catalogues I:350). As this note suggests, the second edition was not a reprint of the first, but rather assembled from extra, overrun stock. In assembling the 1682 volume, the publisher James Courtenay (as Plomer spells his name), reset the title-page and page 112 of the 1679 issue, and added to the text of the 1679 edition thirty-five unascribed poems by the author's contemporaries, identified in Appendix A of my edition (229-230). It is likely that the book's printer, William Downing, was directed by the author or the book's publisher, James Courtenay at The Golden Horse Shoe in Saffron Hill, to print an overrun of the 1679 issue, with a view to bringing out a second edition at a later date. This would explain the absence of the printer's name in the imprint of the second edition in 1682: no printer was needed for the 1682 Female Poems, as overrun stock had been preserved at Courtenay's shop.

Beginning with the bottom of page 112, the 1682 edition is a wholly different text from the 1679 edition. Rather than the verse of a single hand, the later edition, with its many "Large Additions" of thirty-five poems which were not written by Ephelia, resembles a small miscellany of Restoration verse. The second edition of 1682 may have been initiated by the author's brother, as Mary Villiers would never have countenanced such a poem as "The Green-Sickness Cure," in view of her discomfort with explicit sexual material; her poem, "Maidenhead," e.g., is the only unfinished verse in her canon because she cannot sustain a libertine persona.

Self-dedications

When Mary Villiers executed the genius stroke of dedicating her book to herself in 1679, she was acting contrary to world convention, but not without precedent. Mary Elizabeth Brown in Dedications: An Anthology of Forms... (NY: Putnam, 1913), in her discussion, "Dedications to Oneself," offers several pre-1679 precedents of the self-dedication; e.g., John Marston, Scourge of Villainie (1599) and George Wither, Abuses Stript & Whipt (1622). Self-dedications after 1679, in Brown's anthology, include A Narrative of the Life of Charlotte Charke, Written by Herself (1755) and a play by Voltaire as "Gabriel Grasset," Les Guebres (1769).

Section IV. Hermeneutics

Negative Evidence

Conspicuous, but explainable, negative evidence exists in "My Fate," an autobiographical lyric in which "Ephelia" laments the loss of both parents, "snatch'd" by Fate "in their tender age." Yet, both parents of the present candidate were not young when Lady Mary 'lost' them to circumstance: Buckingham was 36 years old when he was murdered by Felton, and "Kate" Manners was in her mid-30s when she was ordered by Charles I to surrender her children to his care. In accordance with the present case, the poet's original line was most likely, "Thou snatch'd my Parents in my tender Age" (emphasis added); but because this disclosed too much identifying information, "my" was changed to "their" to deflect attention from the author of the book, one of the most famous young orphans-wards of her day.

Ann Finch's "Ephelia."

In all fairness to my colleagues, let me briefly provide a summary statement on Finch's "Ephelia." Myra Reynolds in 1903 suggested that Ann Finch's Ephelia might have been Frances Thynne, Lady Worsley, daughter of Francis and Henry Thynne. Ellen Moody in 1999 tendered a counter-hypothesis in Ann Finch's sister-in-law, Frances Finch Thynne, Lady Weymouth (www.jimandellen.org/finch/poem111.html). While it certainly follows that Ann Finch's Ephelia could have been almost any woman of the exclusive Worsley-Thynne-Finch circle at (or associated with) the Longleat estate in Wiltshire, Mary Villiers is the most persuasive candidate, to date, for Ann Finch's Ephelia. Three important pieces of information about Finch's Ephelia in the opening lines of Finch's most polished moral and cultural critique, Ardelia's Answer to Ephelia, who had invited her to come to her in the town..., offer rather stunning support. Here are the opening lines of Finch's 247-line poem:

Me,

dear Ephelia, me in vain you court

With all

your pow'rfull Influence, to resort

To that

great Town, where Friendship can but have

The few

spare hours, which meaner pleasures leave.

No! Let

some shade, or your large Pallace be

Our place

of meeting, love, and liberty;

........................................................................

But to those

walls, excuse my slow repair;

Who have

no business, or diversion there;

(1) As this poem's title and text state, Finch presents Ephelia as a resolute urbanite, who does not reside at Longleat or any other great country house, but rather in "that great Town." (Mary Villiers's principal place of residence was London, thus making her the appropriate female addressee of Finch's extended moral and cultural critique of certain strata of citified Englishwomen. (2) Finch's Ephelia lives in a "large Pallace" (this is Whitehall, Mary Villier's second home as a de facto member of the royal Stuart line; she was, in truth, a frequent family resident at Whitehall all of her long life. Longleat, though one of the great English treasure-houses, was not a "large Pallace"). (3) Finch's Ephelia enjoys high, public status, "all your pow'rfull Influence" (with the exceptions of Queen Catherine and the queen-mother, Henrietta Maria, few women at this time had more "pow'rfull Influence" then Mary Villiers Herbert Stuart, Duchess of Richmond & Lennox, a best friend from childhood of Charles II and, according to my case, the most highly-placed woman writer of the second Caroline court. Ann Finch's clever juxtaposition of "Ephelia" and "court" in her poem's incipit may also support my argument.

Until more persuasive arguments come to light, I must deduce that the addressee in Ann Finch's two poems to Ephelia is Mary Villiers, whose affectionate regard for women and for women writers (Katherine Philips, Aphra Behn) is expressed in her elegant octavo of 1679. The Ephelia poems in Finch's canon are a new window on the sororal bonds among literary women nobles during the second half of the seventeenth century.

Gloves

Alert readers of Gramont's Memoirs of the Restoration court know that women's gloves, as well as their muffs and fans, were sometimes used as agents of clandestine conveyance. Such amorous conduits had a long tradition in pre-Restoration literature, of course, as discussed by Paula Sommers in "The Hand, The Glove, The Finger, The Heart: Comic Infidelity & Substitution in the Heptameron," which appeared in Dora Polachek's collection, Heroic Virtue, Comic Infidelity: Reassessing Marguerite de Navarre's 'Heptameron' (Amherst: Hestia Press, 1993), 132-41. See also James V. Mirroll, Mannerism & Renaissance Poetry (New Haven: Yale UP, 1988).

Anne Gibson (née Shepherd), Dwarf of Lady Mary Villiers, and Court Page (1621-1709)

While her potential role in Mary Villiers's clandestine literary activities must remain speculative at present, I have discovered a few relevant facts. Evidently, Anne Gibson was more than a Court curiosity and employee. She enjoyed close ties to Stuart court culture through the agency of her husband (also a dwarf), Richard ("Dick") Gibson (1615?-1690), an acknowledged portrait-miniaturist and Drawing-Master to the princesses Mary and Anne. Shortly after the death of Charles I in 1649, the Gibsons were taken under the protection of Philip, Earl of Pembroke, and resided at Wilton. Anne Gibson and Mary Villiers, who herself resided at Wilton in the mid-1630s, shared some traumatic life experiences. Few Londoners did not.

In addition to profiles of the Gibsons in the Grove Dictionary of Art and Bryan's Dictionary, see J. Murdoch and V.J. Murrell, "The Monogrammist, DG: Dwarf Gibson & His Patrons," Burlington Magazine, CXXIII (1981), 282-9.

V. Ephelia in English Song

Restoration Court Composers

For career biographies of Thomas Farmer, Moses Snow, and William Turner, see Ian Spink (for Snow and Farmer) and Don Franklin (for Turner) in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians ("Grove 6"), General Editor Stanley Sadie, 20 vols (London: Macmillan, 1980).

An unsigned manuscript copy of a setting of Ephelia's popular song, "When busy fame o're all the plain," overlooked in my edition's apparatus, is in the collection of the Folger Shakespeare Library, Folger MS W.b.515. I am grateful to Mary Ann O'Donnell and Elizabeth Hageman for bringing my attention to this setting. For additional locations of Ephelia settings, published by the Playfords, see my edition (265-8, ills.). The Playfords are generously profiled, with a secondary bibliography, in Grove 6, and discussed in a principal source, Ian Spink's English Song: Dowland to Purcell (NY, 1974).

Gibbs

For details on the distinguished career of Dr Cecil Armstrong Gibbs, see Stephen Banfield's profile of Gibbs in Grove 6 VII:35-38.

Reconstructing the steps by which a researcher arrives at new information is usually instructive:

I found a citation to the Gibbs "Ephelia" setting in the World database at the NYPL Research Facility. I then requested a copy of the published score from the Sibley Music Library, Eastman School of Music, Rochester, NY. I then contacted the setting's publisher, Boosey & Hawkes, London, for the mailing address of a Gibbs relative. The publisher put me in touch with Gibbs's daughter, Mrs E. Ann Rust of Gloucestershire, England, who, recognizing the name "Ephelia," directed me to soprano Georgina Colwell, Hersham, Surrey, who sent me inscribed copies of her recent CDs, which include her performance of Gibbs's setting. Colwell wishes to be considered an enthusiastic member of the reconstructive wing of the Ephelia debate. See my note on Colwell, Restoration (Fall, 1997), 114.

Early Musicwomen

Colwell's recorded performance of Gibbs's "Ephelia" setting contributes to the present renaissance of interest in musicwomen of the early-modern era, the subject of a successful new collection, Women Making Music...1150-1950, edited by Jane Bowers and Judith Tick (1987). I also might mention a few useful locations of new audio adjuncts to print scholarship on early women writers: (i) recent compact diss on the musical writings of Hildegard of Bingen, a Medieval abbess and mystic (e.g., A Feather On The Breath of God, Hyperion label, 1981); (ii) Julianne Baird's recordings of selections from Jane Austen's eight manuscript songbooks, preserved at The Austen Memorial Trust in Chawton, England (Jane's Hand, Vox Classics label, 1996); and the ongoing good work of two successful musical groups, The Dryden Ensemble (Princeton, New Jersey), and Music Before 1800 (New York City). The latter group has organized performances of works by or about women of this era, such as "Voices of Women" (The Drawing Center, SoHo, NYC, 18 January 1993), which included settings from the verse of Aphra Behn, Elizabeth Hampden, "My Lady Killingrew," [Anne Killigrew?], et al.

_______